A Community Garden for All: A History of the Ballard P-Patch

Maria Dolan

We respectfully acknowledge that we gather and garden on the traditional land of the Coast Salish peoples, specifically the dxwdəwʔabš (Duwamish) peoples, past and present. We honor with gratitude the land itself and the Salish peoples.

The Ballard P-Patch is one of Seattle’s oldest and largest community gardens and provides a 0.66-acre area of open space in Northwest Seattle for cultivation and repose, not far from the shores of the Salish Sea. This land was home to sovereign Coast Salish nations until 1855 when a treaty was signed at Point Elliott by territorial governor Isaac Stevens and representatives from the Duwamish, Snoqualmie, Lummi, and other Indigenous nations. The treaty, which the United States has never fully honored, exchanged tribal lands for reservations and rights to fishing and hunting for Native peoples.

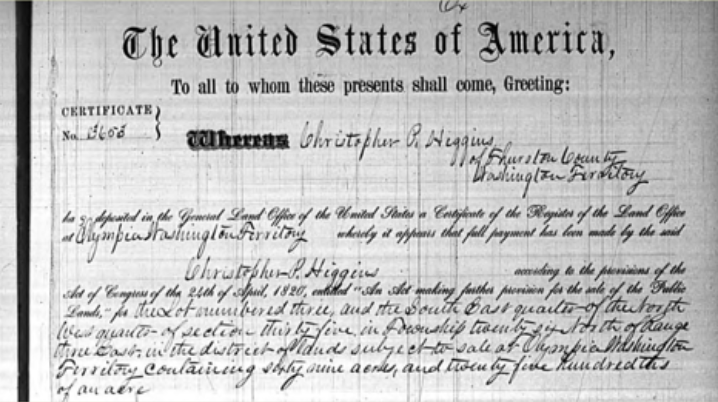

In 1872, a Stevens employee, Christopher P. Higgins, claimed the first title to the parcel of land that became the Ballard P-Patch.

In 1872, a Stevens employee, Christopher P. Higgins, claimed the first title to the parcel of land that became the Ballard P-Patch.

No documents have been found indicating that this land was used for commercial purposes or anything other than agriculture.

What is known is that the land has never been paved over or developed in the modern era.

Early Community Gardening

|

Nearly one hundred years later, this modest parcel remained undeveloped when the adjacent Our Redeemer’s Lutheran Church purchased it in 1967 from the Catholic Church.

|

Then, in 1976, Our Redeemer’s congregation preserved this plot as a garden for the next forty years, by founding the Ballard P-Patch and leasing it to the City of Seattle for a mere $1/year.

|

Many community gardens broke ground across the United States in the 1970s. This particular site offered both benefits and challenges for new gardeners. Empty space with ample sun exposure was the primary draw, but the unimproved soil required work. Typical of Seattle’s hilltops, the soil is Vashon Till, a sediment left behind when the last glaciers receded from this area about 11,000 years ago

It is composed of densely compacted, gravelly, sandy silt to silty sand with clay, scattered cobbles and boulders, and stringers of sand or gravel. This local soil is often low in nitrogen and calcium, two nutrients plants need, because ample rain tends to wash away those soluble ions.

|

Neighborhood gardeners applied to the city, claimed plots and dedicated themselves to yanking weeds, composting, and amending the soil without synthetic chemical pesticides or fertilizers—a rule at all Seattle P-Patches.

|

Their efforts filled the garden with radishes and snap peas, strawberries and tender lettuces, eggplants, tomatoes, sunflowers, dahlias, and more.

|

The First Decade

Tina Cohen, who moved in nearby, landed her first garden plot here in 1979. She recalls that there were smaller houses and many rentals in the neighborhood. She also remembers cooler summers, making it harder to grow eggplants, tomatoes, and other heat-loving crops.

Gardeners also remember a more loose-knit garden community, with an emphasis on self-sufficiency and modest goals. “Our first fundraiser was a car wash,” says Louise Carbonero, who also began gardening here in 1979. “Does that tell you anything?”

Gardeners also remember a more loose-knit garden community, with an emphasis on self-sufficiency and modest goals. “Our first fundraiser was a car wash,” says Louise Carbonero, who also began gardening here in 1979. “Does that tell you anything?”

Back then, the city rototilled the garden each year after the fall harvests, and re-staked garden beds each spring. Winter crops were impossible since no one was guaranteed the same plot from one year to the next. With the city’s hands-on management, there were few expenses, but perhaps less cohesion among gardeners. Gardeners conducted a few educational activities, including composting demonstrations and fruit tree pruning classes, but held no large events.

Some neighbors adjusted slowly to the community garden. Archives at Our Redeemer’s include a letter to the church in 1980 from a neighbor complaining about the high grass at the P-Patch and a request to mow. In 1983, other neighbors, offended by the smell of the compost requested that the church have the pile moved to the center of the property.

Some neighbors adjusted slowly to the community garden. Archives at Our Redeemer’s include a letter to the church in 1980 from a neighbor complaining about the high grass at the P-Patch and a request to mow. In 1983, other neighbors, offended by the smell of the compost requested that the church have the pile moved to the center of the property.

A Project to Bring the Garden New Life

By the mid-1990s, some long-time gardeners recall that the P-Patch was sinking into neglect.

“In the core areas, either no one was gardening in them, or they were abandoned,” said Len Eisenhood, who secured his plot in 1996. Gardeners rallied behind the idea of creating a central patio as an improvement, to create a place where both gardeners and visitors could relax and enjoy the beauty and bounty. Kathe Watanabe, who also began gardening at the P-Patch in 1996 and helped create the patio, recalls that she found inspiration for the idea from a visit to the Queen Anne P-Patch.

Watanabe wrote a request for a matching grant for the project from Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods, and several garden members, including Eisenhood, formed a work party and built the central patio in 1997, with excellent intentions but uneven skills.

“We had a professional bricklayer give us instruction on how to lay down a herringbone pattern using brick. And we began in a corner. And as we got about 10 feet out, we realized it was going cattywampus and we had to take up the whole thing and start over,” says Eisenhood.

“In the core areas, either no one was gardening in them, or they were abandoned,” said Len Eisenhood, who secured his plot in 1996. Gardeners rallied behind the idea of creating a central patio as an improvement, to create a place where both gardeners and visitors could relax and enjoy the beauty and bounty. Kathe Watanabe, who also began gardening at the P-Patch in 1996 and helped create the patio, recalls that she found inspiration for the idea from a visit to the Queen Anne P-Patch.

Watanabe wrote a request for a matching grant for the project from Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods, and several garden members, including Eisenhood, formed a work party and built the central patio in 1997, with excellent intentions but uneven skills.

“We had a professional bricklayer give us instruction on how to lay down a herringbone pattern using brick. And we began in a corner. And as we got about 10 feet out, we realized it was going cattywampus and we had to take up the whole thing and start over,” says Eisenhood.

Yet the central patio served its purpose. “I recall, at the end of a long day, working with Kathe and we were putting in the final screws on some uprights…and I had a great feeling of satisfaction, a feeling that this would be the call to bring life back into the space,” says Eisenhood.

The P-Patch Comes into its Own (2000-2021 and Beyond)

The Ballard P-Patch flourished in many ways over the following two decades.

The patio hosted picnickers and at least one wedding, which proceeded while nearby gardeners weeded and harvested among the beans and sunflowers.

The patio hosted picnickers and at least one wedding, which proceeded while nearby gardeners weeded and harvested among the beans and sunflowers.

|

What became the garden’s signature community event, the Art in the Garden festival, began in 2001, when Len Eisenhood imagined it as a way to help the Ballard P-Patch introduce more people in the neighborhood to the garden.

|

“I decided just to try something small,” he recalls, “to get some art from my friends who are artists, maybe make a poster, and we’ll see what happens.”

|

At the first event, strong winds blew the art off homemade easels, but it was a beginning, and from there it grew.

Art in the Garden became the social centerpiece of the garden year, a summer open house where the public strolls the garden, enjoys local artists and musicians, and shares laughter over beer and bratwurst.

It is also a modest fundraiser for the P-Patch. Over the years, the P-Patch waitlist grew so long that gardeners agreed to reduce plot sizes to allow for more gardeners, giving space to the 90 individuals and families who now garden here.

Another 1,300 square feet was dedicated to a Giving Garden, where food is grown specifically for donations to the Ballard Food Bank and other free food programs. “Ballard P-Patch was in many ways on the forefront of Seattle P-Patches,” says former Department of Neighborhood’s P-Patch Program supervisor Rich MacDonald. “They took the lead in working with the city to reduce the size of the plots to allow more families into the gardens at a time when we had long waitlists. They also took the lead in fundraising and organizing to increase accessibility in their garden,” he recalls.

The P-Patch community devoted thousands of hours of volunteer time on many other projects to turn this P-Patch into the oasis it has become, by demolishing the old tool shed and building a new one, adding water stations, building the information board, developing the flag plaza, building a stage, reconstructing a composting operation, and erecting a south wall graced with a mural by local artist Ryan Henry Ward.

The Capital Campaign to Save the Garden

“We weren’t going to raise it in car washes and bake sales.” -Cindy Krueger

Some forty years after gardeners planted their first seeds here, the Ballard P-Patch community faced an enormous, unexpected challenge. Our Redeemer’s, the landowner, announced their need to sell the parcel to pay for costly church renovations, including earthquake safety measures.

Grow Northwest, a nonprofit land trust organization that owns several P-Patch sites around the city, stepped in to gauge enthusiasm for trying to raise the approximately $2 million required to purchase the land from the church.

“There are only a handful of P-Patches left that are leased by private property owners,” notes Michael McNutt, Grow’s Treasurer. “The church really didn't want to lose the property, but they needed to raise those funds and that was probably the only way they were going to be able to pay for their repairs.”

Devastated gardeners weren’t sure if raising that money was even possible.

“It was very stressful and distressing to think that that would happen after forty years and now…the community would fall apart. That was the worst,” said Mary Jean Gilman.

“It was very stressful and distressing to think that that would happen after forty years and now…the community would fall apart. That was the worst,” said Mary Jean Gilman.

“I thought, ‘there’s no way we're going to raise $2 million to save the garden,” recalls Philip Osborne. But he recalls, another garden leader immediately took up the challenge.

“My initial thought was: this can't happen,” said Cindy Krueger, a leader in the ultimately successful campaign to purchase the property, “Something must be done.”

Many approaches led to dead ends. For instance, Seattle‘s Department of Neighborhoods was unable to offer any financial support. “There just wasn't that kind of money in any city coffer to purchase that land,” says Rich MacDonald.

“My initial thought was: this can't happen,” said Cindy Krueger, a leader in the ultimately successful campaign to purchase the property, “Something must be done.”

Many approaches led to dead ends. For instance, Seattle‘s Department of Neighborhoods was unable to offer any financial support. “There just wasn't that kind of money in any city coffer to purchase that land,” says Rich MacDonald.

On May 17th, 2019 supporters launched their campaign to “Give the Gnome a Home” at the Ballard Syttende Mai parade, decked in gnome hats and waving signs and banners. Local small businesses offered support through fundraisers. Behind the scenes, a number of gardeners worked more than full-time to organize the campaign, engaging a non-profit consultant and land conservation attorney to determine a strategy and cover legal bases.

The gardeners landed their first large grant in December 2019, from the Cooper Newell Family Foundation, a small, neighborhood-based non-profit. “Our foundation funds arts, education, and the environment. So, in this case it was a three out of three hit for our mission statement,” said Laura Cooper. And more donations, large and small, flowed in over coming months--every dollar confirming that this P-Patch is valued by the community.

Each month brought new challenges, but small successes also piled up.

A donation of $10,000 came in through the Roy and Sandra Bueler Living Trust.

An anonymous donor offered a $100K matching grant for all donations larger than $10,000.

36th District Washington State Representative Gael Tarleton toured the P-Patch and encouraged the group to apply for a Washington State Community Projects Grant.

Tarleton felt strongly that the garden was worth saving. “It was yet another symptom I saw happening in our city where the pressures for development and the value of land for development were outpacing the ability for communities to hold on to community anchors,” she says. “It’s always about not just the value and benefit today but the consequence of losing it. You will never get it back again.”

Tarleton felt strongly that the garden was worth saving. “It was yet another symptom I saw happening in our city where the pressures for development and the value of land for development were outpacing the ability for communities to hold on to community anchors,” she says. “It’s always about not just the value and benefit today but the consequence of losing it. You will never get it back again.”

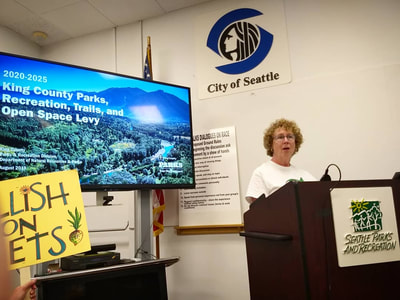

Still, this wellspring of donations was unlikely to add up to $2 million without a large grant from a major funding source. Hope arrived with a visit to the garden from King County Councilwoman Jeanne Kohl-Welles and her Chief of Staff Adam Cooper. Kohl-Welles recognized the importance of the garden and recommended several county funding measures with the potential to fund much of the purchase.

“What I found so compelling was, one, that there was so much community effort involved,” recalls Kohl Welles. “An outpouring of love and support for this parcel. And the other thing was the amount of food that was being grown for donation in the Giving Garden.”

|

A meeting with Ingrid Lundin, the grant manager for the County’s Conservation Futures grant, gave the gardeners the boost they needed to pursue this matching grant, which was earmarked for saving open space.

In early 2020, the gardeners submitted a $1.256 million proposal to the King County Conservation Futures Tax (CFT) grant program and waited months for a response. |

Art in the Garden was tabled for the year, due to pandemic restrictions, and fundraising shifted away from soliciting local businesses, many of which were struggling.

While there were signs that the grant would be approved, timing was difficult. Our Redeemer’s needed the land purchase to be completed in summer 2020, months before any King County CFT funds would be available, so garden leaders sought a bridge loan., The unique nuances of the transaction—a nonprofit trying to purchase a community garden in the middle of economic uncertainty from the pandemic—created challenges. Leaders were again met with multiple setbacks, until a stroke of good fortune at the eleventh hour occurred in the form of a long-term friendship between Pastor Kathy Hawks and John Zmolek, CEO of Verity Credit Union.

“For me it was divine synchronicity— I've been part of this potluck group that's been meeting for 28 years, every month,” says Hawks. And one of my dear friends who's part of that is John Zmolek, CEO of Verity Credit Union. I was relating one night about what was going on with trying to get a bridge loan. I said, So John, is there any chance?”

Verity Credit Union agreed to provide a two-year loan with 4% interest to GROW to purchase the property, and GROW officially purchased the property from Our Redeemer’s on August 31, 2020. The P-Patch was purchased, but there was still major work to be done to finish raising the funds to pay off the bridge loan.

In November 2020, the gardeners received the happy news they had been waiting for: the King County Council approved $1.256 million from the Conservation Futures Tax program, and the garden fundraising was nearly complete.

What Will the Next Chapter Be?

During the summer, I'm there at 6 or 6:30. And it's just an incredible time to be there. All the birds are out. And it's got this great smell to it. And it's just very peaceful and relaxing. It's just a beautiful place. -Gardener Stacia Lee

|

The garden is preserved for all to enjoy. Visitors to the P-Patch can fire up the barbecue and grill a meal, read and relax on one of the garden chairs, or simply walk through and take in the sights and smells of this gathering place. The garden also serves as a learning place for those curious about composting, planting strategies, and other garden topics.

|

A seed swap is coming this spring. And volunteers are always welcome at the Giving Garden and monthly work parties. (link to calendar page of website?) “I hope people realize that this is really a public garden, and we welcome people to walk through and enjoy the beauty,” says Kathe Watanabe, a gardener at Ballard P-Patch since 1996. “It's there for them, it's not just for us.”

The gardeners’ goal is to leave the land and community even better than they found it, for all who are part of the garden’s next chapter.